Amanda Rottier has spent her career shaping products that define the media landscape. Before her current role as head of product at CNN, she was at the New York Times for eight years, where she was a product leader for NYT Cooking. Cooking was a pioneer product as the Times learned to work at the intersection of the newsroom, the engineering team, and the business department, and today it has a user base of millions. We talked to Rottier about the early days of the app and the role community played in its evolution.

Small edits made for clarity.

Upstatement: Can you tell me a little bit of your story? What’s your editorial interest? Why did you gravitate to media?

Amanda Rottier: I joke that people in my position wanted to be journalists in another life. So I have this very deep respect for journalism. I started my high school newspaper with a friend of mine who is now a published author and writes for the Times.

I just really believe in truth-seeking and holding people to account. I believe that free flowing of information is critical for society to work. I always say [my contribution] is that I want to keep journalists paid. I lived through that rise of the internet and how it slowly eroded the business models of newspapers, the bankruptcy, and it was terrifying. That really solidified to me how important it was to figure out how we could keep this going—or we were just going to be swallowed by capitalism and the internet.

It’s very necessary. So let’s talk about the role that NYT Cooking played in saving journalism.

AR: [laughs] Yes. I would say somewhat, but…

That was a joke, but it’s great that the New York Times has a larger view of all the different legs that support journalism—the entertainment legs—and knows they’re actually important parts of the package. It all supports the free flow of information.

AR: Yes. I hate to say this, but people don’t pay for news about war. They want to pay for content that’s about something they want to do or be. Part of what I felt with Cooking was, “Yeah, I’m charging for recipes because that’s what allows us to put reporters in war zones.”

If you did everything on an ROI basis, you would only cover celebrity news.

You’re not really going to know, ever, until it’s live.

Let’s start with some basics on NYT Cooking. The key roles, who was involved in the launch…

AR: Cooking started out of this McKinsey project about how the New York Times could find new revenue streams, essentially. McKinsey found different areas where we could invest…and teams were built out to explore all these different ideas. Cooking was a small team. The original product lead was Alex MacCallum. I think Alex was the only product person. They maybe had one and a half designers and a handful of engineers. Very, very start-up-y. A big piece of this was [Times editor and columnist] Sam Sifton being involved on the editorial side and working close with Alex at that time.

There was a huge database of recipes going back to the 1960s, and that was the product. I remember a really massive push to digitize all those recipes and get them formatted and online. Like, let’s just get an audience. So it was really just a focus on getting the recipes online in a format that users would want to engage with, and it was a super beta product initially.

Looking at some of the early press releases, a big part of the marketing was around the number of recipes and Sam talking about what they chose to include.

AR: That was the vision at that time; it was a digital cookbook. This is the era pre-Tasty, when food content was starting to become a big deal on the internet.

There are a lot of factors with food content in particular. Search was a big deal because that’s how users find recipes. So setting up the site and content to be very SEO friendly was important. Our social strategy, even before we invested in video, was a really big piece of what we did in those early days. Those were the big levers. There was basically no marketing budget.

With no marketing budget, how did you grow it?

AR: Search was by far the biggest driver. We had a ton of search authority with the New York Times. We didn’t have to be on the New York Times, we just had to be under the domain. And that’s exactly what we did.

We had this workflow where our marketer met with editorial before the weekend. The weekends were always the big times when people searched for things to cook. So we’d decide, “This is what we should promote in the social sphere this weekend because this is hitting, we know it’s summer, it’s very seasonal. Let’s pull up some of these recipes and make sure they have a photo.”

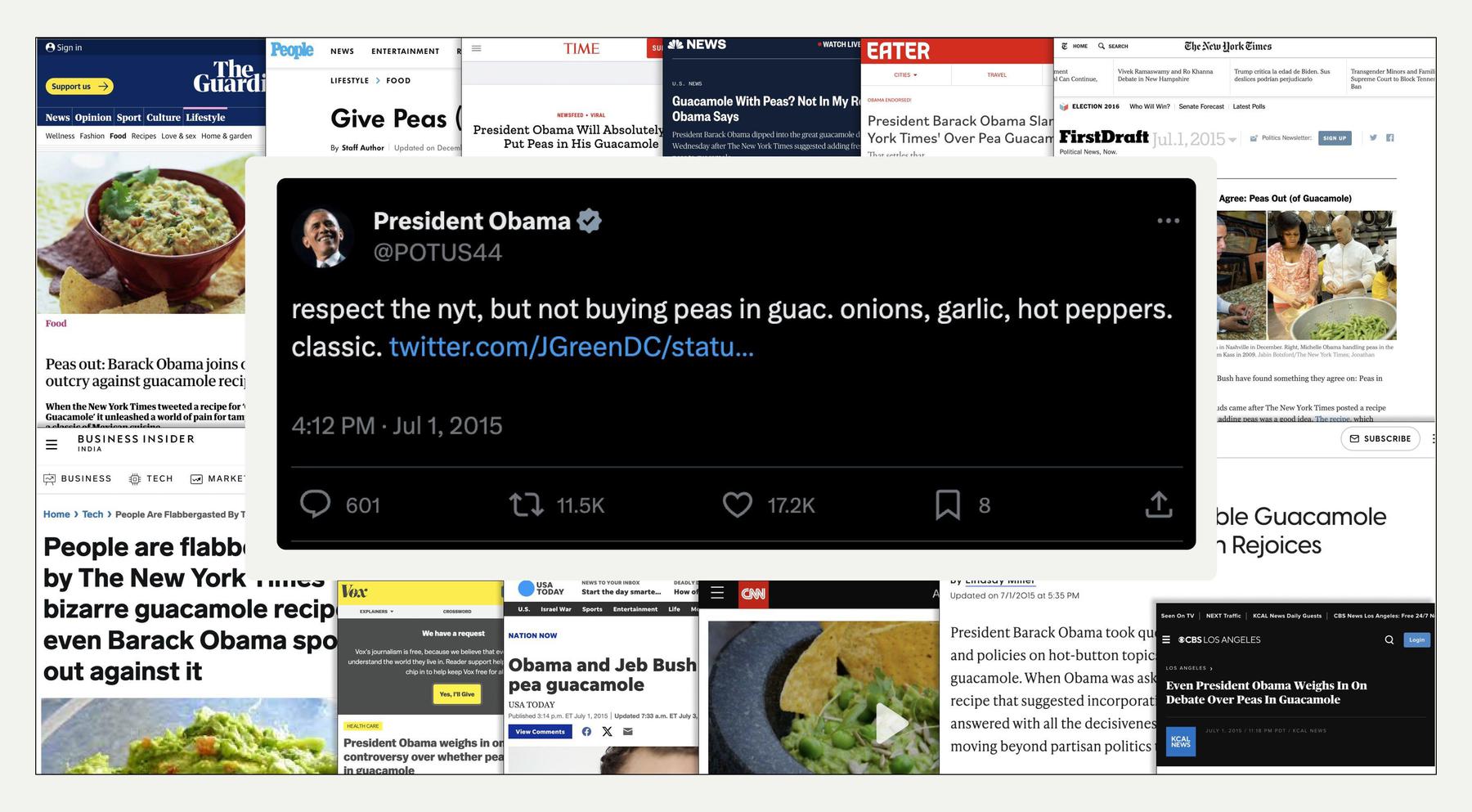

The hard part with recipes is that most people don’t have the budget to go and develop all new recipes. It’s a very labor-intensive process. You need experts. But we could take an old recipe, do a shoot, and put it back out there. And people thought, “Oh my God, it’s a new recipe from the New York Times,” even if it was an old recipe from 1950. So a lot of rejuvenating was going on, and we had some big hits. Then Obama commented on our pea guacamole recipe and people lost their minds internally. We were like, “Oh my God, we’ve hit it big. We’ve got 5 million unique users. This is the big time.”

We did also leverage the New York Times site, of course. Every time the food desk wrote about anything, it had to link out to the Cooking product for the recipe versus just publishing the recipe right there in the New York Times. And we had this great newsletter, which was all Sam and his voice and the community. Sam wrote five of them a week. I think it’s still one of the biggest newsletter that the Times has, and he developed this cult following that really led to growth.

A lot of start-ups have a cold-start problem, where they’re starting from zero and don’t have any audience, and it’s such an interesting contrast that your challenge was learning how to take advantage of having this big platform in the New York Times.

AR: Yes, but as we got into monetization, it became really critical to show that most of our traffic actually wasn’t from the New York Times. We had to show that there were enough people outside of the New York Times who would want to pay for a cooking product. And actually, we had a lot of search authority on our own. Most of the traffic came directly from search, not from the New York Times, which was a common misconception internally and externally—showing that we could be a standalone brand was critical to then deciding we could charge for it, which then helped the Times build value for the larger subscription bundle.

That makes sense. We helped Chris Kimball from Milk Street launch his brand from scratch and do the initial paywall, and those calculations sound familiar.

But let’s go back to Obama and the pea guacamole, because we haven’t talked about community yet. We’ve talked about a lot of the levers that you had to pull for growth. What was the community strategy in the beginning? What role did you think community was going to play?

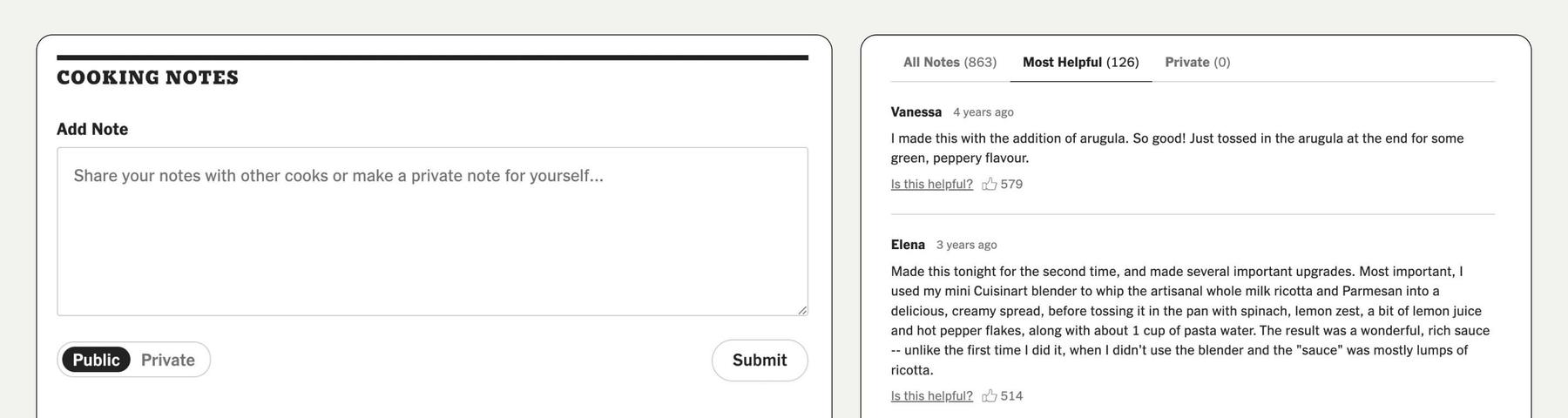

AR: It was always on a pitch deck that community was important. But at the very beginning, it was not a huge requirement at launch. We launched Notes (our version of comments) much later.

Can you explain more about what Notes are?

AR: Notes are comments—but Sam really did not want to call them comments. He wanted them to be called Notes. Any other food blog, or Allrecipes, many [comments] would be unhelpful, like “Love it” or “Hate it.” So we were intentional about the type of comments that made it on the site; they had to be helpful and contribute to the community. For example, how you can improve or modify a recipe: “Hey, I didn’t have this ingredient, so I used this instead.” Or, “Hey, if you have this kind of oven, you should try this.” So it was meant to be useful annotation that added value to the recipe.

Did that social engineering work?

AR: I think so. I don’t know if a regular user would even notice that it was called Notes, but we moderated it very specifically. As a user now, that’s the first place I check. By being intentional, even if nobody else notices that we call it Notes, it was an expectation setting internally of how to handle the comments coming in.

We’ve seen this in our work too—you can successfully guide the community to give you more of what you want through subtle things. Sometimes the help text is not just “Comment” or “What did you think?” It’s specific, like, “How did you cook this recipe?”

You can ask for the type of feedback that you want. And then as you’re moderating and people are seeing other comments, communities will model what they see in the community, so it builds on itself.

Do you remember why you didn’t launch with some of the community features?

AR: Just an MVP decision. With that small engineering team, they needed to get the site out. Getting the recipes online was the first thing.

What role do you think community ultimately played in the success of Cooking?

AR: It was a major factor. To decide to put a paywall around recipes was a very difficult decision. A lot of people didn’t believe it was possible because recipes are very commoditized. But when you started to interact with users in our community and see how much people loved the recipes, we felt a lot of confidence that this was something that people would pay for.

That was a critical moment when community—that there was a community—was a really big deal. And then later on, post-paywall, it’s still a big factor. Would it be as successful without it? I don’t think so. There was something about the way that we invested in the brand, and the way that people responded to Sam and his voice, and the way that people used the product—this was community, whether or not people thought they were in a community. It felt like you were part of something.

Very few people commented and very few people were super users. But I think that’s how community works. There’s always going to be that powerful core, and then anyone who touches it gets the sheen of that, and it helped build the brand and the voice, and all of that was so important in attracting those casual community people.

It’s a digital product. You can go back. You’re not producing cars.

That’s a principle we’ve seen too. Maybe 5 percent of the community is actually generating 80 percent of the content, but being a lurker is still being part of the community. Maybe a common misconception is that people think, “Oh, well, I need millions of people commenting.” You actually need a small community that’s dedicated and consistent and trusted.

So if a majority of these people were not from the New York Times, you built that community from scratch. What was it like in the early days of cultivating the consistent group of people who were commenting?

AR: I do think the overlap between New York Times people and Cooking was pretty big, to be totally fair. But the core New York Times user skews slightly older and slightly male and more coastal. Cooking was much more female, much younger, more Midwestern. So we were definitely reaching a new group of people.

In the early days it’s not that we weren’t thinking about community, it was just that we focused so much on voice, on Sam’s voice, and how we were posting and how that was all coming together. And we focused a lot on really making sure the recipes actually stood up.

And then, over time, we knew a ton. I could tell you everything about people that cook. By the end, I was like, “I don’t want to ever think about this again!” We did a ton of user research throughout the time there.

It’s cooking, right? It’s not rocket science. But there was a watershed moment where we did a huge market segmentation study of the whole market of cooks. We split them up and we said, “Okay. This is who we’re going after.” It was a very specific persona, and it wasn’t based on demographics. It was all based on user needs or behaviors.

Demographics versus psychographics.

AR: Exactly. It was much more based on psychographics. For instance, we were not for people who were on diets. We were like, “Okay, we can still serve some of that because everyone needs calorie count, but we’re not going to be the diet site and we’re not going to be like Allrecipes,” which is a very community-generated site where people could post their recipes and post their own pictures.

We played with that, the community-generated content idea. But ultimately, the real strength was in our brand and the recipes. If we started introducing people coming in with their own recipes it would dilute what we felt was core to the product. That’s just a very non-New York Times thing: we’re not going to put content on our site that’s not our content.

If you did everything on an ROI basis, you would only cover celebrity news.

This gets into an interesting interaction between the community and the editorial content and how they support each other. Could you go a little bit deeper on the relationship between the community and the recipes that you’re publishing, the personalities that you have there, and how you set up that relationship for success?

AR: It really started with Sam. He had his finger on the pulse. That’s the job of an editor, to understand the moment, but he also wrote this newsletter, which just captivated an audience. We used to laugh that the boomer ladies loved him. They were obsessed with him. We’d give him such a hard time. But it’s true, and we realized that if just one voice was so successful, we have all these other voices. Let’s expand that. So [Times food columnist] Melissa Clark got a little bit more involved.

The idea is that they’re journalists first, it’s journalist-first content. We are not food bloggers, we are journalists, and that’s how we approach developing recipes. That was the really big differentiator in our content strategy…the fact that we were the New York Times reporting recipes.

Cultivating personalities is a community principle that we think about a lot. Part of the relationship isn’t just with a platform; relationships and network relationships are with people. And what I’m hearing you say is that people formed relationships, not just with the quality of the recipes, but with Sam and Melissa and everyone.

AR: Yes, and I think the trust was there. The trust that the recipe was going to be good, that it was reported on with the same authority of the rest of the New York Times. In some cases, we had people like [former Times columnist] Alison Roman or already established food people, but a lot of them were just interesting people. It was not a strategy to take all these influencers and make them become part of the New York Times.

A new platform creates opportunities for new stars to emerge, right? Twitter is totally different from TikTok, which is different from Instagram, and you have different stars on there based on what their strengths are.

AR: Yeah. The Food52 app, in the beginning, tried to be the Instagram for food where anyone could share photos. We were stressed out about that. But I think what was smart was that we just doubled down on what we were good at. We weren’t going to become Facebook or Instagram. And so let’s stop chasing that tail. If we had gone down the path of trying to be something that we weren’t, I think we would’ve failed, frankly.

It’s important to understand who you are.

AR: And what your value prop is. That was the key. What did we offer? We weren’t going to be a social network. We were never going to be able to do that, but we have content. We’re never going to beat people on the tech. We just won’t. You can’t look like a junky website, but aside from that, if you make the content good, everything else will follow.

I think it’s a common misconception that a community product is a social media product, but in fact there are a lot of gray areas between them. You have to try so many different features to find your niche. A lot of swirl. When did you feel like you were ready to start charging for subscriptions?

AR: We were probably ready a year before we actually did. The hurdle for charging for subscriptions was more internal than anything else. There was a lot of resistance, discussion, consensus building that had to happen. We were hitting 10 to 12 million uniques a month. There was a belief that maybe we should just try to keep going and be the biggest food site [and not risk losing users with a paywall]. Emotionally, I was ready the first day. I knew. I was like a dog with a bone. I was like, “We’re putting a paywall up. We’re putting a paywall up. If it’s not for the paywall, I don’t want to hear about it.”

Getting the team focused, getting the Cooking team believing that they could launch a paywall—it started with: how are we going to make money? We considered every single idea: “We should do e-commerce.” Ultimately, we did take a test-and-learn approach. We even set up a fake paywall at one point. Like, let’s just see if people will go down this path of registering and entering their credit card. And once they got to the page right before the credit card, we would swap it out and say, “Guess what? You got it for free.” That’s how we measured the intent. And we had a registration wall, which was an important precursor.

We landed on a freemium model where certain recipes were in front of the paywall and certain ones weren’t. And that was something that we could flex. It’s different from the New York Times, which has a meter for a maximum number of articles. But you can’t put all of the Thanksgiving recipes behind the paywall. We felt like we needed to have some flexibility.

The paywall was a bit of a guessing game. But when we launched it, it worked. That gave me great faith that you can charge for pretty much anything. Most people would say, “Why charge for recipes when you can get them free anywhere online?” But there was a cachet, there’s a community, there’s something you’re a part of, there was a promise of quality, there was Sam Sifton reaching out every day in his newsletter.

Do you remember what it felt like when the day you put the paywall up? Were you like, “Oh my gosh, our 12 million people are about to vanish…” Or were you confident?

AR: I definitely had a plan B. If it doesn’t work, we’ll just take it down. It’s a digital product. You can go back. You’re not producing cars and it comes off the lot, right?

So when did you know it was successful after launching?

AR: We knew in the first few days. The numbers coming in were so enormous we couldn’t believe it. Every month, we were crushing every number. The goal for the first year was 50,000 subscriptions, and I think we got to around 120,000 in the first year.

What were the key performance metrics that you were looking at in those early days? Was it simply subscription numbers, or were there other things?

AR: It was definitely the subscription numbers. We had a forecast and we had a business model backing it up in order to fund the team. We had to be meeting certain thresholds. Part of being in that beta group was that you had to go to the board and get sign-off.

I lived and breathed the drivers. Any good subscription business, that’s what you’re going to look at, right? You’ve got how many uniques coming in, from where, how many are engaged? And then you had the conversion rate and retention.

What’s the biggest lesson that stays with you today from New York Times Cooking?

AR: People will pay for a lot of things, so give it a shot. That was a big lesson for me.

Also, you just try it to see what happens. You’re not really going to know until it’s live. People get a little precious, especially in editorial-driven organizations, and that’s okay, you should be precious. But I think it’s my job to push the business as much as I can.

Another lesson—business model 101. We were so scrappy in those early days of Cooking, and we built all kinds of different models. Some were close to what ended up happening, some weren’t. That’s the beauty of doing business models. It’s almost like its own creative venture that shows you what’s possible.

What inspired you in the early days of the app? And what’s inspiring you right now?

AR: Working at the New York Times was very inspiring for me. Just being a part of all that—it was the most fun you could have as someone who loved being in journalism and solving problems and being around smart people. So just that energy there was big for me.

I am also pretty competitive, so if you give me a goal, I really want to meet it. And they took a chance on me. I was on the strategy team before I got the job on Cooking, and I hadn’t been a product manager before. I felt like I needed to prove myself.

So yeah, that’s what drove me then. And today, it’s about the same. I want to do better than I did yesterday. Corporations have a bad rap right now. Corporate America is seen as being a bad place to be, and I really want people to enjoy working here. Life is short. Capitalism sucks, but you gotta show up at work. You have to do a job. I’m not going to be a TikTokker. I want to be, but then I’m not going to be able to pay the rent, and I’m not going to be able to pay for my kids’ school. So let’s just make the best of a bad situation!

In Launch Lessons, we talk to founders, product managers, and creators about work that builds communities and pushes brands forward.